Optimization, by nature, is an exact science – strategize, execute, analyze. Those who are good at it are methodical, detail oriented, and observant. However, in every industry, there are people who think they know more than they actually do.

This has become widely known as “The Dunning-Kruger Effect” and is a common optimization bias.

What is The Dunning-Kruger Effect optimization bias?

The Dunning-Kruger Effect is a term established by a Cornell University research study.

Conducted by sociologists Dr. David Dunning and Dr. Justin Kruger in 1999, it studied a cognitive bias in which a person fails to see their own deficiencies or gaps in knowledge. As a result, they can overestimate their abilities and competence.

In psychology terms, it’s similar to anosognosia, but Dunning chose to dub this common bias meta-ignorance, or “ignorance of ignorance.”

(Colloquially, it’s also earned the nicknames “Mount Stupid” and “Smug Snake.”)

As a concept, it sounds a bit harsh to assert people are incompetent. But it’s an optimization bias that can happen to anyone.

As Dunning and Kruger write:

“Poor performers—and we are all poor performers at some things—fail to see the flaws in their thinking or the answers they lack. When we think we are at our best is sometimes when we are at our objective worst.”

A note about common optimization biases

It should be explained that no one is exempt from experiencing optimization bias at some point in their professional lives. So if you’re biased, you’re not alone.

Jeffrey Eisenberg, CEO at BuyerLegends, offers some insight on optimization biases in general:

“There are two components to each bias. First is confirmation bias, for example, our tendency to seek out confirming information while ignoring everything else.

The second is a meta-bias, the belief that everyone else is susceptible to thinking errors, but not you. This bias blind spot is what blinds you and me from our errors.

Most companies assume they’re giving customers what they want. Usually, they’re exhibiting a blind spot bias. Bain & Company showed this when they studied the delivery gap.

A few years ago, when Bain & Company surveyed 362 firms, they found that 80% believe they deliver a ‘superior experience’ to customers. But when they asked their customers, they believed only 8% are really delivering superior experience.

One of my favorite examples of this blind spot is the Dunning–Kruger effect. This bias was first experimentally observed by David Dunning and Justin Kruger of Cornell University in 1999.

They reported: ‘The miscalibration of the incompetent stems from an error about the self, whereas the miscalibration of the highly competent stems from an error about others.’ You might want to remember that bias as a slogan: More confidence, less competence!”

We encounter incompetence regularly. Sometimes, despite our best intentions, we are incompetent in certain areas. There’s a ton of real-world examples, which we’ll get into in a minute.

Two Truths and an Irony

There were two inescapable truths put forward by the sociologists’ study:

- Ignorance is all around us on a daily basis.

- Those who are ignorant often don’t know it.

In fact, very smart people can still be very ignorant!

From Dilbert, by Scott Adams. Image source

Eisenberg writes:

“Smart people are very good at rationalizing things. Even if they believe them for non-smart reasons. Smart people easily brush off criticism since they are convinced they are right. Being smart, they can probably out-argue most criticism even if the criticism is right.

Albert Einstein said, ‘No problem can be solved from the same level of consciousness that created it.’ We are full of biases, and yet we must strive to overcome them.”

In CRO, this can be especially harmful, as conversion rate success depends entirely upon removing ego from the equation to see revelatory results.

However, there’s ignorance in every industry, so acceptance is the first step to recovery.

The great irony

Of course, the frustrating part of these truths is that you must have knowledge to realize you don’t have knowledge.

As quoted in Forbes:

“The knowledge and intelligence that are required to be good at a task are often the same qualities needed to recognize that one is not good at that task—and if one lacks such knowledge and intelligence, one remains ignorant that one is not good at that task.”

The Dunning-Kruger Effect (a.k.a. “Mount Stupid”)

How did the Dunning-Kruger team run the tests?

Dunning and Kruger examined a subject’s expertise in logical reasoning and grammar by administering 20-question tests. They also assigned each individual subject tasks evaluating their social proficiency and humor.

The humor test was more subjective in some ways, so the results were less defined, but participants in this were asked to rate jokes by funniness. Their answers were then recorded and compared to the joke ratings given by a panel of career comedians.

Once the subject completed these tasks, they were asked to rate their personal performance:

1) In comparison with their peers.

2) Without comparison to anyone else. (For example, how many questions they thought they got right on their completed test.)

The numbers

So what were the test results? High performers usually guessed their percentages fairly accurately, but low performers tended to greatly overestimate their own score.

Logical reasoning test

Performer’s test score: 12%

Performer’s test score guess: 68 %

Grammar test

Performer’s test score: 10%

Performer’s test score guess: 61%

(Though they rated their actual grammar knowledge to be around 67%.)

Humor test

Once again, because humor is subjective, these tests were less easy to measure, but suffice it to say that those who didn’t make good jokes kept making them anyway.

What about the high performers?

Those who scored highly on the tests often underestimated their knowledge due to a lack of data for comparison.

Essentially, because they couldn’t see how everyone else was doing, the high scorers assumed the low scorers were doing as well as them on the test, or better. (This is known in the scientific community as the “false consensus effect.”)

However, once given the ability to compare when asked to grade the grammar tests of their fellow subjects, their opinion changed.

(It should be noted, however, that getting new data for comparison did not change low scorer’s self-evaluations. In some cases, the low scorers actually increased their self-evaluation score.)

A brief session designed to train low performers did help them evaluate themselves more accurately, however, so it should not be seen as insurmountable.

Arthur Wheeler and lemon juice

Arthur Wheeler’s embarrassing blunder is regularly used to depict this optimization bias concept in action.

The Catalog of Bias offers the example below:

“In 1995, Arthur Wheeler made the critical error of confusing the ‘invisible ink’ properties of lemon juice with the visual properties of everything else and walked into a bank with lemon juice smeared all over his face.

Robbing two banks over the course of a single day, he was reported to be incredulous when the police caught him later that same day, using CCTV footage of his face. “But I wore the juice!”, he exclaimed […]

Tragically, Mr. Wheeler tested out his theory first with a Polaroid camera. Sure enough, the ‘selfie’ he took printed as a blank image, almost certainly due to defective film.”

Other examples of Dunning-Kruger

Scientific American offers some examples throughout history to illustrate the pervasiveness of ignorance and the overestimation of one’s position, abilities, or skill. We’ve thrown them into a bullet-pointed list below for some easier reading:

-

- “The Trojans accepted the Greek’s ‘gift’ of a huge wooden horse, which turned out to be hollow and filled with a crack team of Greek commandos

- The Tower of Pisa started to lean even before construction was finished—and is not even the world’s farthest leaning tower.

- NASA taped over the original recordings of the moon landing.

- Operatives for Richard Nixon’s re-election committee were caught breaking into a Watergate office, setting in motion the greatest political scandal in U.S. history.

- The French government spent $15 billion on a fleet of new trains, only to discover that they were too wide for some 1,300 station platforms.

- The Wild Wing mascot of the Anaheim Ducks caught himself on fire attempting to leap over a burning wall (cheerleaders pulled him from the flames and he returned to action later in the game, unhurt).”

Forbes.com similarly offers some modern examples where this effect plays a significant role:

- “One study of high-tech firms discovered that 32-42% of software engineers rated their skills as being in the top 5% of their companies.

- A nationwide survey found that 21% of Americans believe that it’s ‘very likely’ or ‘fairly likely’ that they’ll become millionaires within the next 10 years.

- Drivers consistently rate themselves above average.

- Medical technicians overestimate their knowledge in real-world lab procedures.

- In a classic study of faculty at the University of Nebraska, 68% rated themselves in the top 25% for teaching ability, and more than 90% rated themselves above average (which I’m sure you’ll notice is mathematically impossible).”

A side note

There are some limitations to these tests, namely, a subject’s relative understanding of what ‘proficiency’ is. This optimization bias isn’t necessarily a reflection of someone’s lack of intelligence; more so, it might be a lack of understanding of what constitutes “skilled.”

As The Catalog of Bias notes:

“The point is that we judge our own performance based only on the markers of skill that we already know and think about. Most people know what F1-driving ability looks like, and can confidently say they aren’t at that level.

But in terms of general driving ability, if we don’t know the small details that might make a good driver, we’ll never include these qualities when assessing our own ability.”

Relevance and impact on CRO

How can you tell if optimizers are suffering from this unintentional bias?

Aaron Orendorff did an insightful piece for Unbounce on how to spot fake CRO agencies and “experts.” He interviewed CXL’s Peep Laja, Talia Wolf from GetUplift, and several other thought leaders in the CRO industry. If they can’t spot a fake, no one can.

The main takeaway is this: true CROs know that they don’t know everything. They’re aware of possible optimization bias. They listen to the data and don’t try to force it to tell them the story they want to hear.

Some CROs go about running and managing CRO programs without full knowledge of everything required, and in doing so allow for the Dunning-Krueger optimization bias that messes them up further down the line.

Optimization professionals will not fake data or manipulate it incorrectly. They’ll account for sample size, length of the test, the source of traffic, and other mitigating factors.

For example, many optimizers go for obvious fixes first, hitting home run changes right off the bat.

They alter glaring mistakes or identify clear areas for improvement, but eventually, those big changes resolve. Now, all the low-hanging fruit that was once so easy and rewarding to change is no longer obvious without finding new data sources.

This can deflate their confidence first gained by taking out the low-hanging fruit. (Craig Sullivan dubbed this the “Trough of Disillusionment” because many optimizers at this point must have a reckoning with their skill sets.)

Really, the only way to overcome this period is to acknowledge that not all tests will be obvious and that they take time. Diversify your data stream; using quantitative data is great, but what about qualitative data like customer interviews? Those are also enlightening.

Uplifts aren’t the only thing you can learn from, and sometimes the uplift results don’t mean much. Discernment is key.

Conclusion: how can true optimizers avoid this?

The trick is the outsmart your cognitive bias – stop talking and start listening to the data. If the data says your idea doesn’t work, let it go. It’s not personal. Don’t get married to an idea unless you have the data to back it up – and even then, use caution. The ability to pivot is the ability to stay alive on the web.

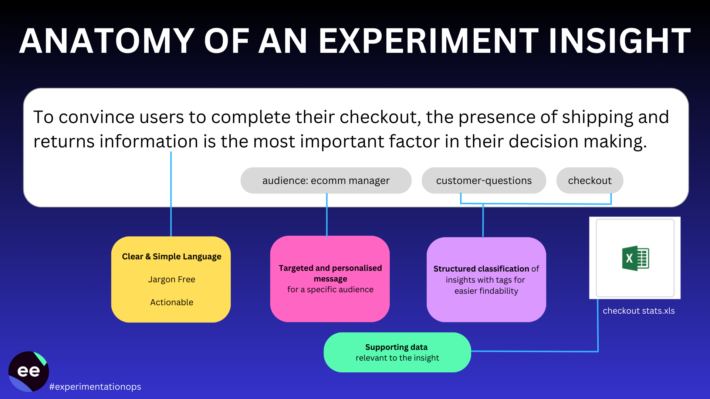

There are three main ideas to focus on: always learn from your experiments (whatever the outcome), don’t overvalue your own ideas, and analyze tests equally.

As Thomas Jefferson once said (quoted by Dunning):

“The wise know their weakness too well to assume infallibility; and he who knows most, knows best how little he knows.”

Similarly, Scientific American Mind writes:

“….Biases are largely unconscious, so when we reflect on thinking we inevitably miss the processes that give rise to our errors.

Mindfulness, in contrast, involves observing without questioning. If the takeaway from research on cognitive biases is not simply that thinking errors exist but the belief that we are immune from them, then the virtue of mindfulness is pausing to observe this convoluted process in a non-evaluative way. We spend a lot of energy protecting our egos instead of considering our faults. Mindfulness may help reverse this.

Critically, this does not mean mindfulness is in the business of “correcting” or “eliminating” errors. That’s not the point. Rather, mindfulness means pausing to observe that thinking errors exist – recognizing the bias within the bias.”

Optimization has no room for hubris. One must get ahead of themselves in order to play the game right. The only real way to counteract optimization bias company-wide, especially the Dunning-Kruger Effect, is to foster a culture of experimentation. (To start the process of this, Eisenberg suggests looking into The Four Stages of Competence.)

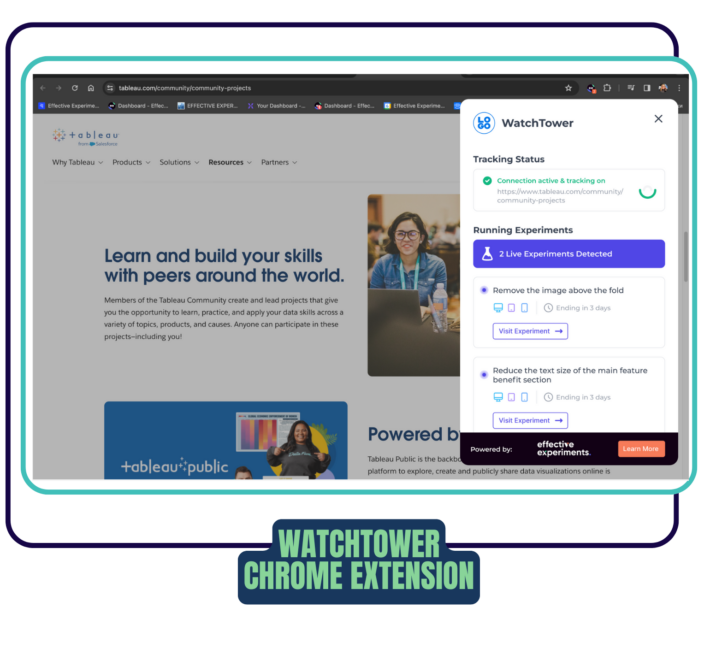

If you’re interested in checking out a great program management platform for your experiments, click here.